Most of humanity’s wealth is built on our ability to bind labor and capital from many people into highly capable institutions. The Dutch East India Company is famous in part for issuing the first stock to the public in 1602. In other words, the company raised money — more money than any other company to date — by enabling thousands of people to buy and sell ownership in simple transactions. The Amsterdam Stock Exchange arose to consolidate the extraordinary trading activity of shares in this one company.1 It’s not a coincidence that nearly all global wealth has been created since this practice emerged.

Investing money can also create remarkable wealth at the individual level. Successful investing doesn’t require creativity or even much work: only some basic knowledge and consistent behavior.

Stocks and bonds dominate the universe of publicly traded assets. In this post we’ll introduce what stocks and bonds are at a fundamental level, and in Parts 2 and 3 we’ll discuss what to do in real life. Let’s begin with stocks.

Stocks are ownership

Those trading shares in the Dutch East India Company had an unprecedented opportunity. It’s now an ordinary part of life that anyone with a bank account can access on their phone. Shares, stock, shares of stock, and equity are all similar terms about owning pieces of a big pie. Shares are the basic units of ownership. To explain the process of becoming a modern public company, let’s rewind about 50 years.

Apple Computer was founded in 1976 by a couple of Steves. Mike Markkula provided much of its early funding, and ownership was divided between a relatively small number of people until the initial public offering (IPO) in 1980. An IPO is by far the most common method for a US company to go public. New shares are sold in bulk to large institutional investors, and sometimes retail investors (i.e., normal people) as well. By increasing the number of shares, the fraction of ownership provided by each share becomes smaller. In exchange, the company receives money from its new owners: Apple Computer raised over $100 million in its IPO. Those who buy shares directly from a company’s IPO are participating in the “primary offering”, and they’re called the “primary market”. Then, the primary market can trade shares with everyone else on the secondary market.

Nearly all trading occurs on the secondary market, where investors buy and sell shares with one another. When you buy shares of Apple (or any other company), you’re buying shares from another investor, not from Apple. As I write this, you can buy a share of Apple for about $230. This represents a very small portion of the company: the total value of all shares is about $3.5 trillion. That number is Apple’s market capitalization, usually shortened to market cap. Apple first achieved the largest market cap in 2011 by passing ExxonMobil, and it has held the crown on most days since then.

The price of a stock is nothing mysterious: it’s the last price at which a buyer and seller agreed to trade in public markets. Most stocks trade very frequently — the daily trading volumes of some stocks exceed a billion dollars — so share prices change continuously when markets are open. A share is valuable because it represents a claim on the company’s assets and future profits. When a buyer and seller meet at a price that they both consider fair, they’re signaling information about the value of that claim. The shifting price reflects the beliefs of many investors about the value of the company, ideally resulting in a “wisdom of the crowds” effect that aggregates information into the price. In Part 2, we’ll explore how your investment approach is influenced by whether you choose to accept market prices or disagree with them.

There is nothing intrinsically meaningful about the absolute dollar value of a share. It provides no info about the company. Costco’s share price is higher than Apple’s, but Apple’s market cap is far larger. Price changes are the concern for an investor.

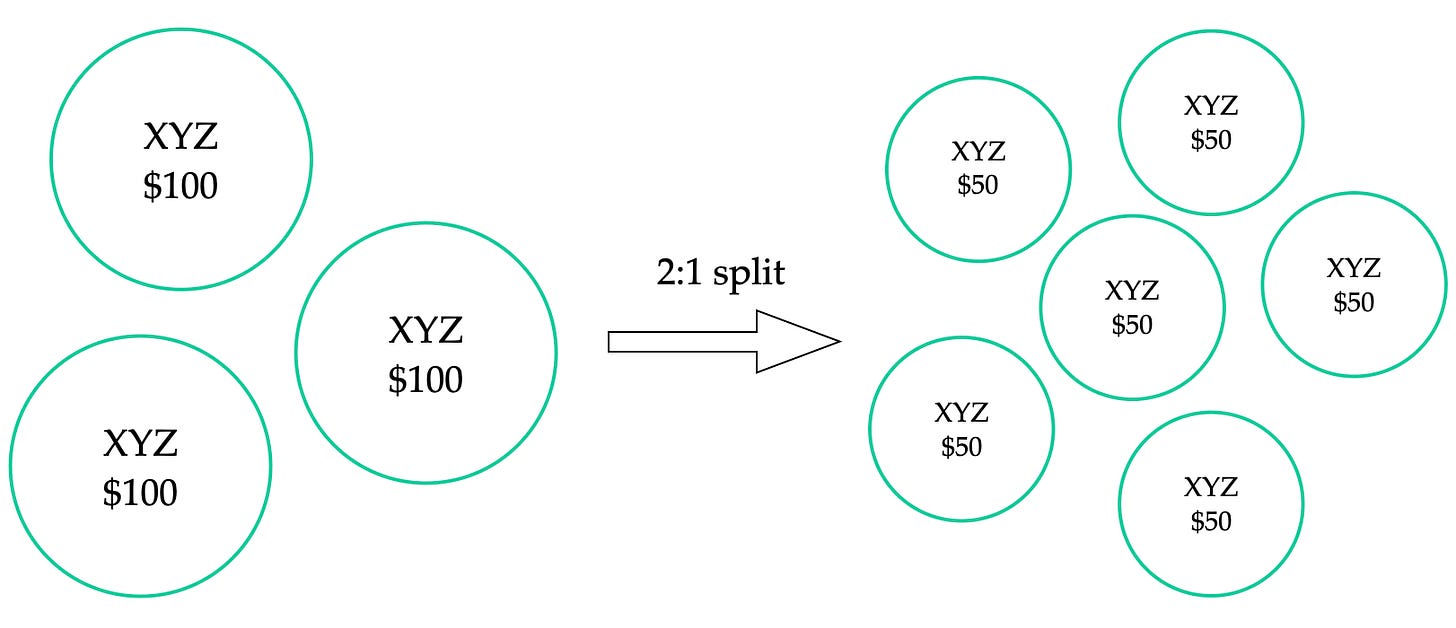

Stock splits illustrate the arbitrary nature of share prices. After a 2:1 split, for instance, all shareholders own twice as many shares and naturally the share price is halved. This is generally conducted to prevent the share price from becoming unreasonably high. Imagine giving four people a quarter of a pizza each. Once they object that a quarter is too big to eat comfortably, you slice everyone’s quarter in half to provide normal slices. But of course they still each have a quarter of the pizza in total. Cutting your pizza in half is a 2:1 split.

Apple stock has undergone five splits, which were 2:1, 2:1, 2:1, 7:1, and 4:1. So without any splits, Apple’s stock price would be 2×2×2×7×4 = 224 times its current price of $230. A company called NVR has never split its stock since it went public in 1985, which is why the share price has reached heights over $9,000.2 In the example above, let’s say you own three shares of XYZ stock each worth $100. After a 2:1 split, you own six shares each worth $50.

Every US-listed stock has a ticker symbol with one to five letters. This helps uniquely identify it: Apple’s ticker is AAPL and Costco’s ticker is COST. Searching a ticker is often the best way to look up info about a stock. As we’ll discuss later, you don’t need to buy (or know anything about) individual stocks to benefit from the stock market.

Bonds are debt

Most people know that banks provide loans in exchange for repayment with interest. With your own money, you can take the role of a bank and invest in debt by purchasing bonds. Bonds are liquid assets that can be traded, although not quite as easily as stocks.

Bonds are an even larger market than equity, with well over $100 trillion invested in bonds worldwide. Most bonds are issued by governments and government-related entities, but there’s also an enormous corporate bond market. Some large corporate bond issuers include Bank of America, Microsoft, T-Mobile, Boeing, and the brewing company Anheuser-Busch.

A bond issuer like the US Treasury sells bonds in order to borrow money. You can buy bonds at auction as they’re being newly issued, or you can buy them from other investors on the secondary market. Anyone who buys a US Treasury bond is owed a series of coupon payments, which usually occur every six months. Payments are called coupons because there used to be detachable coupons on physical bond certificates. A bond’s payments are complete when it reaches a scheduled maturity date.

Upon maturity, the issuer pays a larger lump sum — often $1,000 per bond — called the face value or par value of the bond. Maturities typically range from one month to 30 years.3 Longer-term bonds carry higher risk than shorter-term bonds, which we’ll cover in detail later. The predictable coupon payments of bonds are why they’re also known as fixed income. “The stock and bond markets” is equivalent to “the equity and fixed income markets”.

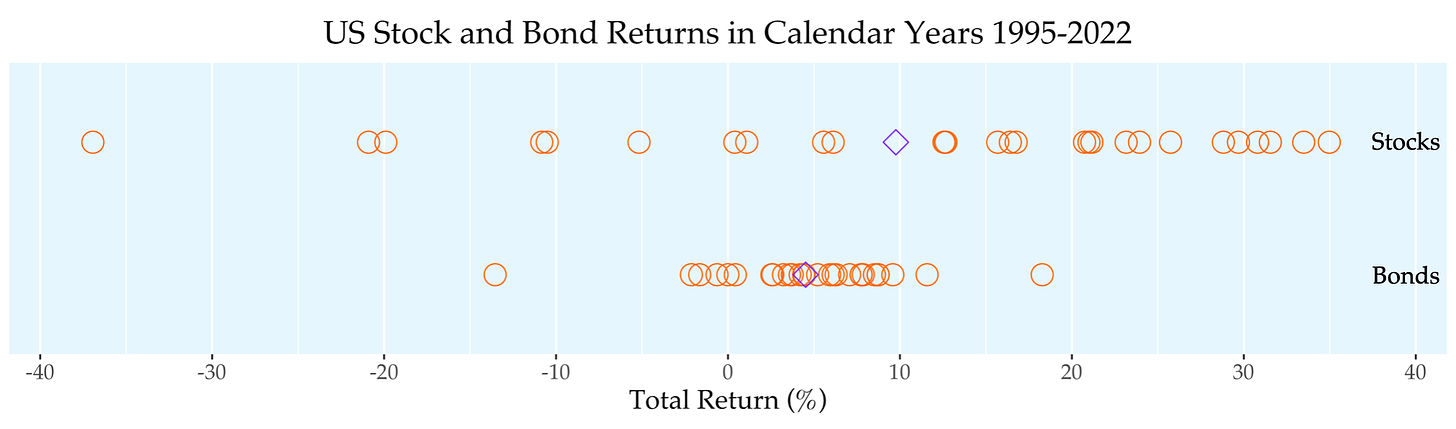

Individual stocks and bonds vary greatly in their risk but, as a whole, bonds have less risk and less long-term return than stocks. You can see in the figure below that most annual US stock returns fell far from the average (purple diamond). The returns for US bonds clustered more closely around the average, but in exchange for the benefit of reduced volatility, the average return was lower.

Bonds are safer in part because, if a company declares bankruptcy, the bondholders’ claim to company assets takes priority over that of stockholders.4 If a bond issuer fails to pay its bondholders in full and on time, this is referred to as default. Most people buy bonds for a relatively safe and boring experience, but defaults can be dramatic.

Argentina is notorious for repeatedly failing to pay its debts. Elliott Management, an investment firm, is most widely known for a long battle with Argentina to collect as much as possible from unpaid Argentine bonds. In 2012, Elliott detained an Argentine navy ship at a port in Ghana with the intent to seize it as payment, but ultimately they were denied possession of the ship. Elliott also plotted to impound Argentina’s presidential plane, but Argentina evaded this in part by hiring private planes instead of using their own. Elliott did, however, win huge profits after compelling Argentina to honor some of its debt in New York courts. From Argentina’s default in 2001 to a final deal in 2016, the bond war lasted 15 years.

Argentina is an extreme case, but it illustrates why bonds that are less likely to be paid back in full command higher expected returns to accompany their risk. US Treasury bonds are among the safest in the world. Some other wealthy nation-states have top credit ratings as well, but the one-month US Treasury is often referred to as the “risk-free asset” to which all other assets are compared. Of course, nothing is strictly risk-free. But the centrality of the US in global geopolitics and finance means that if the US can’t service its debt, no asset is safe anymore and we can all pack up and go home to our bunkers. Although Denmark is a great creditor, its debt payments don’t have quite the same stakes.

State and local governments can also issue bonds. Detroit’s 2013 bankruptcy and several other local fiascos have highlighted that municipal bonds carry greater risk than those backed by the federal US government. Corporate bonds are divided into two broad categories based on credit quality: investment-grade bonds (with comparatively low risk) and high-yield bonds (also known as junk bonds).

The diversity of different types of bonds is dizzying compared to the relative uniformity of the stock market. Most bonds commit the issuer to paying specific dollar amounts, but some are tethered to inflation. Certain bonds can be paid back ahead of schedule. Others adjust their coupon payments based on a shifting interest rate benchmark.

Although the bond market is complex, one benefit is that you can select the degree and type of risk you want. While stocks do vary in risk, there’s no such thing as a “safe stock”. Bonds offer a spectrum of risk that the stock market cannot provide. In the future we’ll discuss the types of bonds that most people should understand.

Capital markets + donuts

Let’s say your friend started a donut shop a few years ago, and just agreed to provide fresh donuts for a local restaurant’s brunch menu. They need money for more space and equipment, but they don’t have much cash at the moment.

Now you know that they have two basic paths to raise money: debt and equity. If they take out debt, they’ll retain full ownership but have to repay the money with interest. If they sell equity, they’ll have no burden of repayment, but they’ll have to share ownership. They could also use a combination of debt and equity funding.

Large companies go public not just to raise money once, but because it streamlines the process of raising money in the future. It becomes straightforward to sell equity (by issuing additional shares) or borrow money (by issuing bonds). It’s a lot more difficult to do that as a private donut shop, but the fundamentals are the same.

Lions and tigers and bears

Oh my, you have a lot of options when it comes to investing. There are thousands of stocks and thousands of bonds, and countless ways to build a portfolio. Is investing a continuous series of stressful and high-stakes decisions? It can be if you want! But for those who value simplicity, the modern investing landscape is extremely user-friendly. You can distill your options to a small menu of well-justified defaults. Rather than buy individual stocks and bonds, most people should buy shares of an investment fund. A fund pools your money with that of many others to purchase a large portfolio of stocks, bonds, or other securities that a small amount of money wouldn’t be able to buy on its own. Some funds purchase international stocks or bonds that would be hard to access otherwise.

Okay, so how do I select a fund? Should I buy one fund or multiple? Wait, what about dividends? And what account should I open? Please, stop crowding around me and I’ll answer all your questions in … Part 2! See you next week.

Further resources

Every Money IRL post is organized in The Omni-Post, and all vocab terms are here.

This series of short videos by Preet Banerjee slowly introduces the basic concepts of investing and assumes zero prior knowledge. I created a YouTube playlist of the videos at that link. (Two videos are skipped deliberately, partly because they contain descriptions that don't apply to modern investments in the US.)

This video by Ben Felix is an outstanding explanation of the principles of financial markets and the general approach to investing that we’ll apply. Even those with some knowledge about investing will benefit from watching.

A summary of all three parts of the gentle intro to investing is here.

The book Why Does the Stock Market Go Up? by Brian Feroldi is a quick explainer on many common questions about the stock market.

—

We love comments here. Tell us what you like or dislike, agree or disagree with. Recall a long story barely related to this post. Ask a question!

Please send photos of your pets if you’d like to see them in future posts. Or suggest a new topic, or say hi! You can email or tap the message button. Stay safe out there.

Email: bright.tulip711@simplelogin.com

—

For more info, see chapter 3 of The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World by Niall Ferguson.

NVR’s price is dwarfed by the six-figure price of Berkshire Hathaway Class A shares (BRK-A), which have never split since the IPO in 1980. Some companies have multiple share classes with different voting power. Berkshire Hathaway has Class A shares (BRK-A) with more voting power and affordable Class B shares (BRK-B) with less. The share class you buy rarely matters unless you care about shareholder voting.

Some countries like Austria, Belgium, Ireland, and Mexico have issued bonds with 100-year maturities. Walt Disney and Coca-Cola have done the same. One Dutch perpetual bond is over 400 years old.