In a taxable account, you pay a lot of tax. Every time you sell an investment and realize a gain or loss, that’s a taxable event. Every time you receive a distribution, like a cash dividend, you’ll owe tax on that.1 A “taxable event” is an event that affects your tax reporting — the info you send in your tax return — and usually your tax liability, which is the amount of tax you need to pay.

Eventually we’ll cover retirement accounts, health savings accounts, 529 accounts for education, and others. They have various purposes, but tax-advantaged accounts share one feature: your trades in the account are sheltered from tax. On top of other benefits, capital gains and distributions are never taxed while the money is in the account, and you can adjust investments as often as you want with no tax implications.

Sounds fantastic. Is there a catch? Yes: tax-advantaged accounts come with restrictions on how much you can contribute and when you can withdraw money. To understand why they’re worth using anyway, let’s explore some details about how investments grow.

Compound growth

It’s easy to illustrate the miraculous results of compound growth, and if you’ve read about finance, you’ve probably seen it too many times. Say we start with a $1,000 investment and assume an 8% annual return. It grows to $1,080 after one year and $1,166 after two years. Leave it for 40 years and whoa, you have $21,725. Even after you’ve done many of these calculations, the result is still a little surprising.

If you’re reading in the mobile app, the equations below might look ugly or even incorrect. It looks much better if you copy the post link into your browser. I hope they fix this!

Compound growth, exponential growth, compounding returns, compound interest — all similar terms. They refer to a process of multiplication rather than addition.

When you earn income from working, you add to your wealth. When your investments grow, you multiply your wealth. This isn’t a gimmicky way to make investing sound cooler. You have to do the math that way, or you’ll be wrong.

When an investment grows by 8%, we can calculate its change in value by multiplying it by 1.08:

What if it grows by 8% two years in a row? We need to start using exponents:

Notice the commonality between “exponent” and “exponential growth”. For a 40-year period, we need to multiply by 1.08 40 times:

You probably see the pattern in how we convert percentage changes to multipliers: an 8% gain is 1.08, a 21% gain is 1.21. The formula to convert a percentage change P to a multiplier M is simple:

If we plug a -8% return into the formula — an 8% loss — it converts to a multiplier of 1 - 8/100 = 0.92. You won’t need this formula for long, because the result is intuitive.

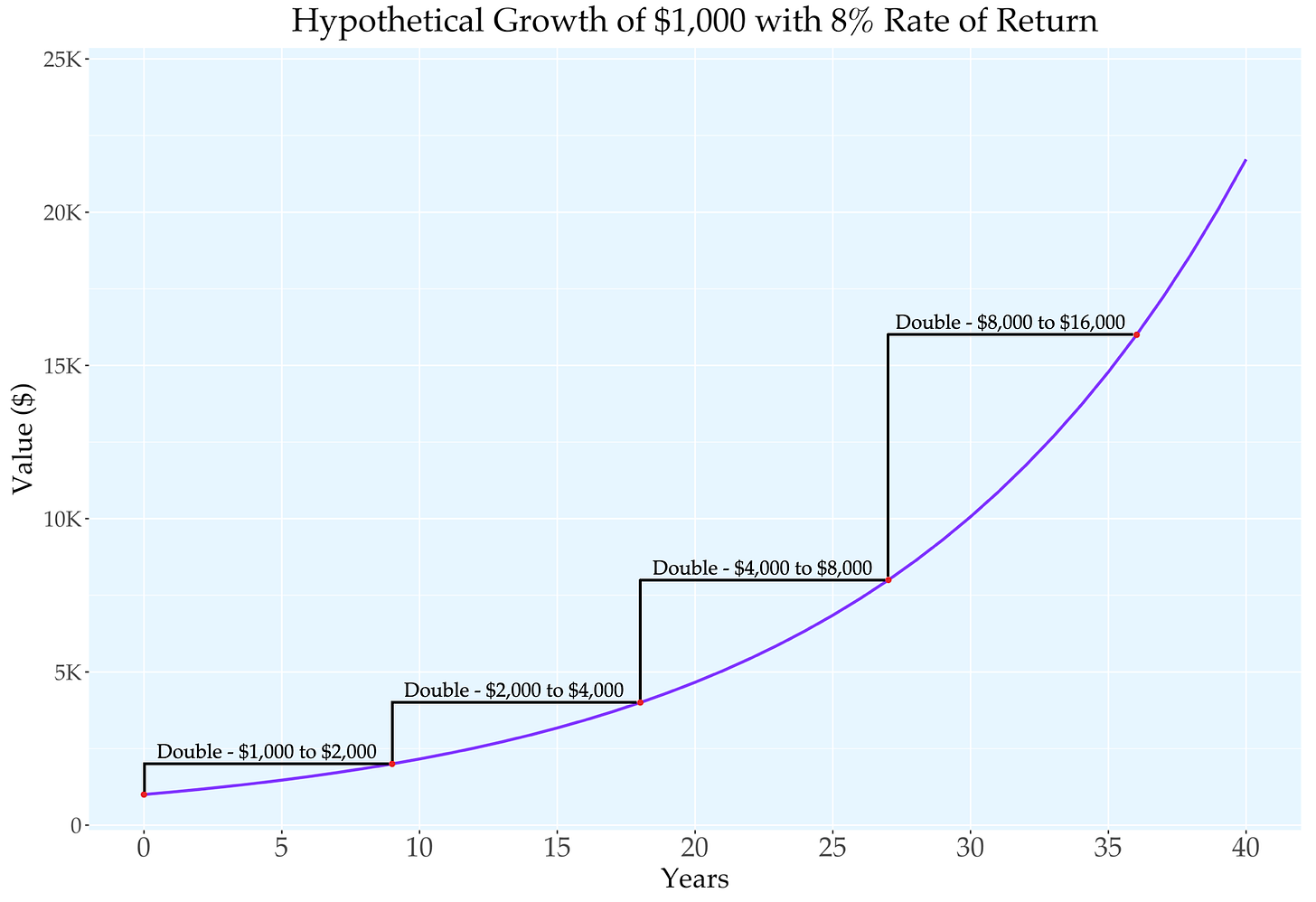

Compound growth is repeated multiplication. A nice way to observe this process is to consider the doubling time of a growth rate. An investment growing at 8% annually will double in about nine years. So it takes the first nine years to grow from $1,000 to $2,000, another nine to double again to $4,000, and nine more to reach $8,000. That’s what constant exponential growth looks like: the value multiplies by the same factor over a given timespan. From the normal human perspective of addition, the growth accelerates: $1,000 in the first nine years and more than $10,000 in years 31-40.

Compound growth is an essential concept, so if you aren’t sure you completely understand it, check out this video.

Okay, compound growth is great, but what’s the point of all that math? Now we can appreciate the magnitude of the advantage we gain by avoiding tax.

To keep it simple, consider a magical investment that increases in value at a constant rate of 10% per year. After each year, it pays out the whole gain as a cash dividend, and falls back to its original value. We love this investment, so we automatically reinvest the dividends.

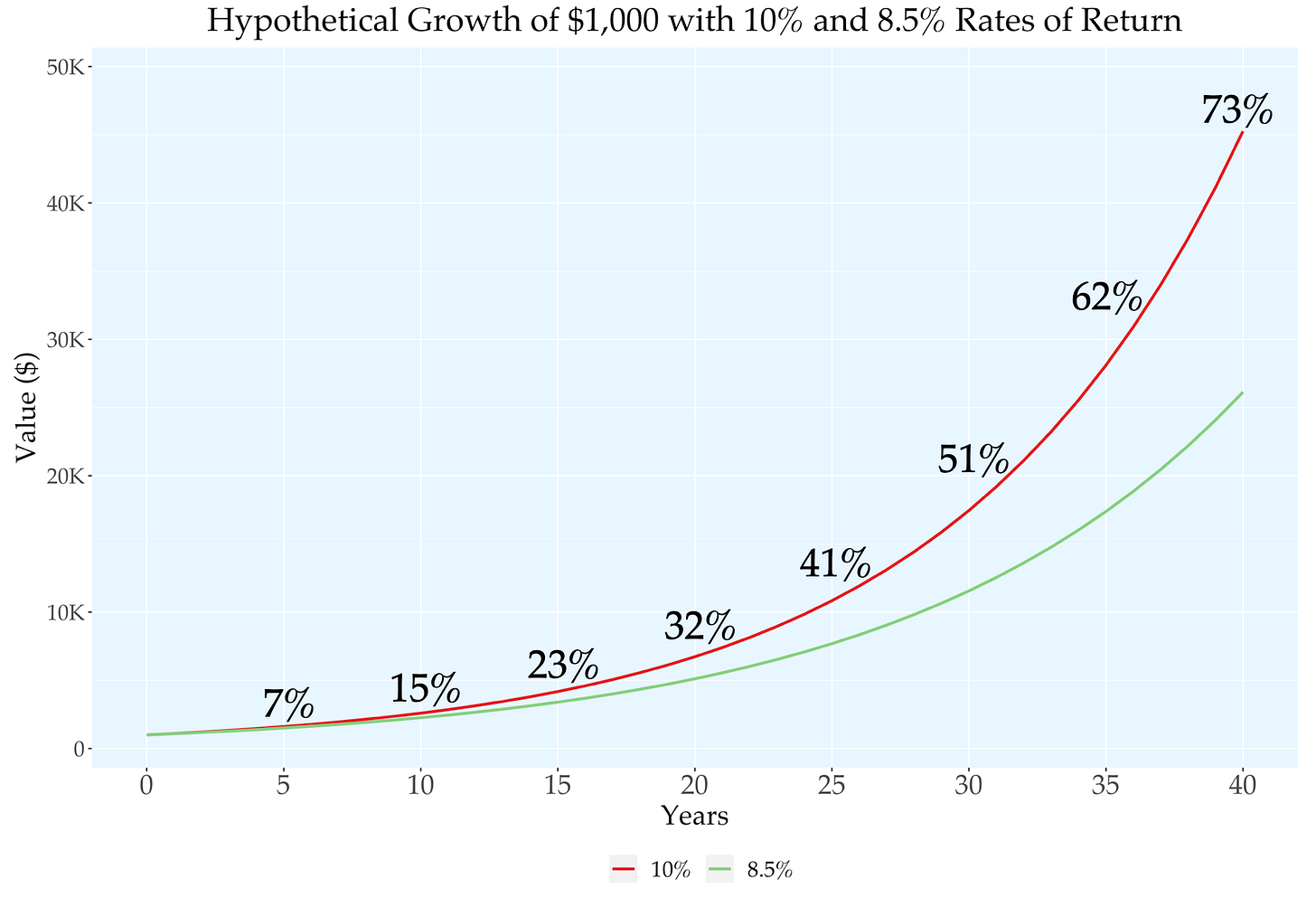

In a tax-advantaged account, we would pay no tax on the dividends. Our annual return would be the ideal 10%. But let’s say that in a taxable account, we pay a 15% tax on the dividend. Our return would be cut by 15% each year, giving us an 8.5% after-tax return. The disparity becomes enormous after compounding for a long time.

The 10% return represents a zero-tax scenario, and the 8.5% return is a taxable scenario.

If we start with $1,000, the values after 5 years are $1,504 with an 8.5% return and $1,611 with a 10% return. The latter value is 7% larger — a real difference, but modest. Every year, the gap expands. The values after 40 years are $26,133 and $45,259 — a 73% difference!

This is just a toy example. There could be so many variations depending on an investor’s behavior and tax situation. We can learn a few things:

Tax-advantaged accounts are extremely valuable in the long run. Losing 15% to tax each year would reduce your long-term gains by a lot more than 15%.

An investment that pays out all its gains as dividends has poor tax efficiency, because dividends are taxed immediately. Deferring your taxable events is a central part of minimizing tax. Hold investments until there’s a clear reason to sell.

When planning your investments in taxable accounts, assume that your returns will be lower due to tax. Many people don’t bother, because tax can be annoying and complicated. Your assumptions about tax won’t be perfect, but they have to exist because tax is real even if you ignore it.

A 20- or 40-year time horizon might seem unmotivating, which is why many people struggle to take advantage of these accounts. The government encourages a long-term mindset by offering such strong tax incentives to set money aside in retirement accounts. Automation helps too: if you set up a system, you don’t need to be motivated all the time.

A multi-decade time horizon isn’t just for young people. You can start withdrawing from retirement accounts at age 59½, but investing doesn’t end at retirement. A healthy 60-year-old can have a 30-year time horizon, because they might live to 90.

Now that we’ve seen the powerful effects of tax-free compounding, we can learn how to use each tax-advantaged account. See you next week!

Further resources

Every Money IRL post is organized in The Omni-Post, and all vocab terms are here.

The White Coat Investor has some of the best resources on using tax-advantaged accounts and investing tax-efficiently. Click here to see their posts on retirement accounts.

Check out this post on the features and challenges of a health savings account (HSA), which has the most tax advantages of any account.

If you aren’t familiar with some of the terms used above, like “taxable account” or “distribution”, please check out the gentle intro to investing. We also have an intro to taxes.

—

We love comments here. Tell us what you like or dislike, agree or disagree with. Recall a long story barely related to this post. Ask a question!

Please send photos of your pets if you’d like to see them in future posts. Or suggest a new topic, or say hi! You can email or tap the message button. Stay safe out there.

Email: bright.tulip711@simplelogin.com

—

A return of capital from a fund, which is rare, is a non-taxable distribution. In addition, some people have low enough incomes that they would not owe tax on a cash dividend. It would affect their tax reporting but not their tax liability.

This is really good stuff! I wish I knew you when I was in my 20's!! Great post.

Boy, they really ARE great!